I have talked in the past of how I dislike linear scenarios and adventure paths. A friend has described strongly-linear games as “walking in a painted tube” because you can see what you are presented, and your only real choices are to go forward or maybe to go back.

I have talked in the past of how I dislike linear scenarios and adventure paths. A friend has described strongly-linear games as “walking in a painted tube” because you can see what you are presented, and your only real choices are to go forward or maybe to go back.

As a general rule, for such scenarios to ‘work’ the PCs have to stick somewhat close to the plot. Deviating from this plot can disrupt the adventure and potentially invalidate prepared material. ‘Derailed’ is the term often used for this circumstance, for good reason, and many consider it a bad thing. I have seen advice in many places about how to prevent this from happening and (sometimes ‘gently’) guide the PCs back on-course, and I have seen advice to mitigate the impact of the PCs’ actions on the plot, and…

Wait. Mitigate the PCs’ actions on the plot? Let’s call that what it is, “stripping player agency”.

Okay, let’s don’t do that. Instead, let’s use a structure that doesn’t depend on players following a particular path. Better yet, let’s use a structure that gives players choices that can change how the scenario plays out.

In other words, don’t plan for a particular story to be told, write the ‘story’ after that tells what happened during.

After determining what the likely goal of the adventure is (I’m assuming this is possible) I determine a structure to hold the encounters of the adventure. This is represented by a graph containing nodes (encounters) and edges (means of travel between the encounters). The ‘edges’ might represent physical paths such as hallways in a dungeon, tunnels underground, or paths in a forest, or they might represent clues or other information directing the PCs between encounters, such as you might find in a village mystery.

If I am designing an adventure that should take a party from one level to the next I might generate a 20-node structure, if I want something to run in a single night or at a convention I might use five (my group plays mostly OSR-style games and could rock through this in a night easy… but we distract easily, while at a con you want something a focused group could get through in a few hours).

For regular use I think ten is usually a pretty good number, to be honest — small enough to run in a single night if we’re really on focus, typically long enough to have some continuity between sessions (we could expect to see two, maybe three nights out of this), and a size such that I might expect to see two such adventures go by between leveling, which feels about right to me for this group.

Note that in an adventure ‘node’ does not necessarily mean ‘room’. It is possible to have two nodes in the same contiguous and easily accessible space, but more likely each node might represent more than one such space. A cavern might have a shrine hidden in one shadowed corner (two nodes in the same space), but more often you find a goblin den consisting of a few linked rooms or an underground mini-temple with a shrine area and some supporting rooms, including a priest’s chamber.

I used to do this manually, but I’ve written a script that will generate graphs for me, up to 26 nodes (because I denote them using letters, and that’s how many letters I have in my alphabet). This script ensures the graph will never be disjoint (thanks for the algorithm, GreyKnight!) and generates a number (which might be zero) of ‘sub-elements’. If there are sub-elements the number is noted in the node they are associated with. I used to draw them so they would stand out, but I found for larger diagrams it both cluttered the image and that many elements could cause the layout engine to do weird things. I run this about a hundred times at once and dump them to a directory where I can quickly skim them and look for graphs I like the look of. Right now I’m hitting about 40-50% that I could work with, and usually about 10 in my top rank.

By the time I’ve reached this point I’ve got some hooks, I know some likely goals (and thus likely targets, and themes). I can start to assign them to the nodes of the graph and populate some others. Some are directly related to the goal, some are more incidental, and the ratio depends on the scenario. In doing so I identify the links between them and what the sub-elements are. Any node that can be reached from less than three paths will either have at least one very simple path or be ‘optional’, not needed in order to complete the adventure… though it may offer a reward that makes completing the adventure easier.

I was thinking of trying to provide a concrete example, but I think that would get too long… in fact, it might be long enough to cover next week’s blog posts. Perhaps it’s time to take the sandbox construction from macro-scale to micro-scale.

In the meantime, perhaps a few examples of what I like and don’t like for adventure structure.

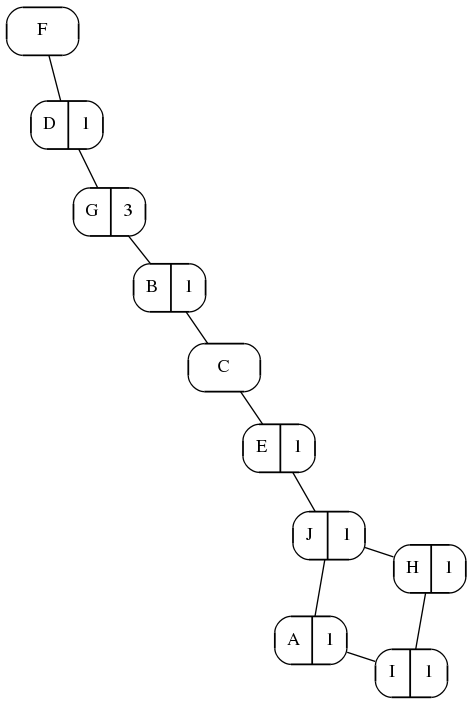

Clearly a degenerate case. It’s damn near a painted tube, and it’s not even painted very much.

Let’s see if there’s a better one.

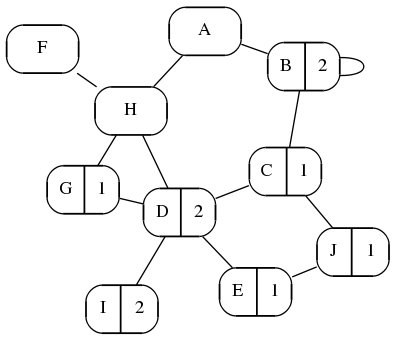

Found one! This one is quite good for my purposes. I might make A, F, or H the entrance and put the goal in J. I might move some subelements around so there is something to find earlier, and I think D needs to either be able to change things elsewhere or be changed by things elsewhere — it’s a very central location and I can expect the PCs to pass through several times. It’s got a few entirely optional places — F and I have only single connectors and thus should be entirely optional but potentially rewarding, and perhaps A, B, E, and G (depending where the entrance(s) is(are)) could be lower priority or have avoidable dangers.

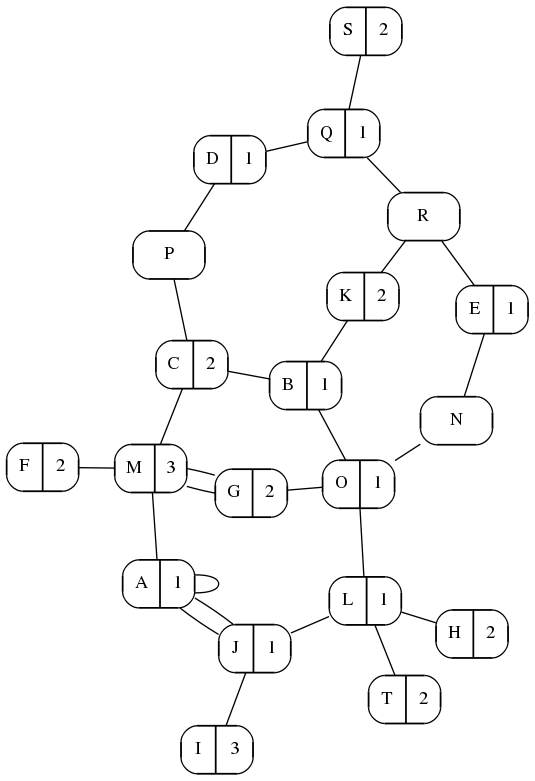

Just for fun, I threw in a 20-node entry. So many paths, so many extras to look at and play with, alternate routes, optional places to explore, and it’s a planarity (which I find aesthetically pleasing). If I wanted to build something that I expected PCs to gain a level in, it might look something like this.

Any chance of sharing this map-generating script?

Good chance, but I should probably ask GreyKnight. He wrote it and if anything I just tweaked it a bit.