This process owes its genesis to ideas I had while reading Justin Alexander’s Node-Based Scenario Design essay. This essay formalized processes I had been applying and helped focus my mind on them… and led to me to some abstractions I hadn’t considered before.

An adventure, a scenario, can ultimately be seen as a collection of related encounters and events where (and/or when) things happen. Being related encounters and events, there should be links between them. These links may be as simple as physical proximity, or might be based around clues found that guide player characters along, or could be something else entirely.

This collection may be represented as a directed graph, as Justin describes in his article (linked above).

The arrangement of these nodes and the edges between them can make a profound difference in how a scenario plays out.

Published Guidelines

As mentioned in my recent article, the guidelines I have seen published tend to be fairly straightforward, and I suspect have encouraged similarly simplistic adventure design.

Linear Adventures

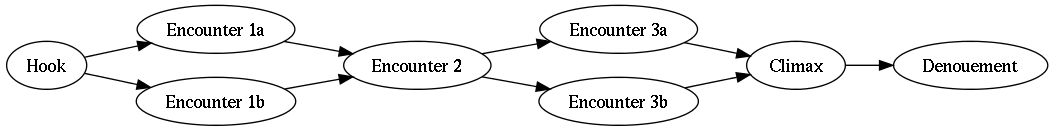

Published guidelines in several sources from multiple publishers appear to focus on adventure play forming a ‘story’. Story structures tend to be fairly straightforward – you have a hook that engages players (or readers), a set of events that build up to a climax, the climax, and a denouement where things get wrapped up.

If drawn as a graph, this might look something like

This is a very easy structure to build on, but can be problematic to play. Deviation from the plot likely means the GM has to find a way to get the PCs “back on track” (woowoo! railroad alert!) or has to start winging it because he doesn’t have material prepared. Neither is really desirable.

I’ll include in this the ‘semi-linear’ scenario, where there are branches in the path but you end up coming back to the same end points.

Better, but still not as good as I’d like.

I think part of the problem may be that people don’t realize (or it isn’t made obvious) that while a scenario can be presented as a story (in linear fashion) after it has been played out, until the scenario has been played out it can be entirely non-linear. Only when the scenario events and encounters have been resolved do you know the path that was taken. Being able to predict likely paths is useful to the GM, but it is not necessary to predict (and especially not to mandate) the path that will be taken.

“Open” Scenarios

These are scenarios where the PCs freely choose whatever they want. I find these dissatisfying because in my experience they generally just kind of wander around. It’s difficult to plan for and prepare much in advance because it tends to be very difficult to predict what is going to happen.

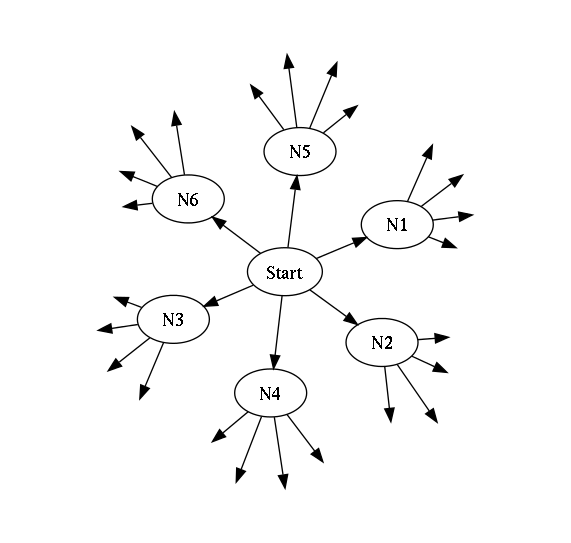

If drawn as a graph, this might look something like

The players have ‘more choice’ in this model, but I find that the difficulty this places on the GM to predict likely paths makes it difficult to prepare later materials. I moved away from linear scenarios to a model closer to this early on, but found it was troublesome because I had to prepare and set hooks from time to time to see if the players were interested in following up… and if they were, potentially change the entire nature of the scenario.

This could also be considered something of an initial state, where the players choose the scenario they want to play and then things become more predictable because they lapse into a more linear scenario. Again, not terribly satisfying, though it does make it easier to prepare and run.

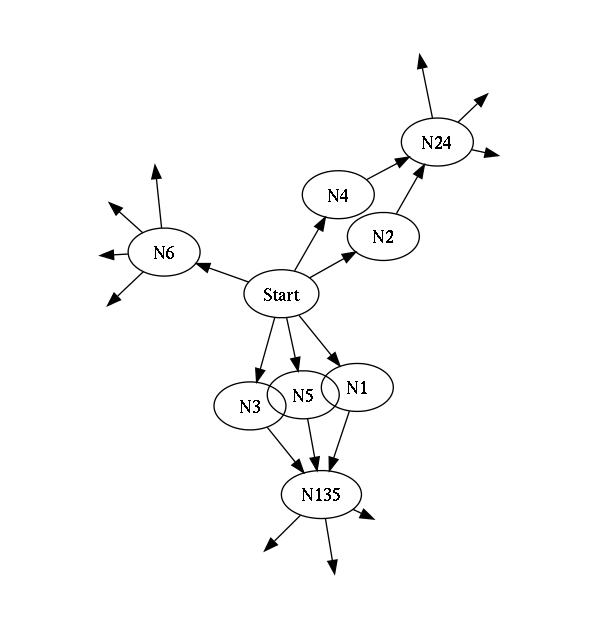

Like the linear model above, there are variants, including some where you combine things again. This might look like

This is better, but still seems insufficient. In order to prepare a scenario with structure like this you may find you have to prepare material that will never see the light of day because no one wanted to go that way. For instance, if the players decide the N6 path is the most interesting you’ll be running the smallest section of the prepared material (and may run out earlier than you want). The N2/N4 paths are a little better because you’ll get to use more prepared material, but then you’re back to a semi-linear adventure. The last group is, in a sense, the worst of them because at least half the preparation for that path alone will likely go unused at this time, and you end up at the same place anyway.

Now, the ‘unused preparation’ isn’t truly wasted if you can reuse it elsewhere. If N5 is a troll lair, you can use that when you again need a troll lair (and it’s always nice to have little pieces ready for use when you suddenly find they would be useful – I used to collect such things for when I had to wing it)… but it’s nice to be able to use the things when you actually prepare them.

Not-So-Published Guidelines

I recently reviewed some DM references, looking for some guidelines for adventure design. They mostly covered the options above, but there were some small references to “matrix adventures” where, instead of having a particular path through the encounters, they can be done in more or less arbitrary order until the goal is met. Unfortunately, they mostly only touch on the subject; it seems the writers expect the linear or open scenarios to be more common.

This is unfortunate, because I think the ‘matrix adventures’, slightly refined, have a lot of potential. I prefer to call them ‘cohesive scenarios’ rather than ‘matrix scenarios’.

Cohesive Scenarios

In a cohesive scenario, the players are presented with a situation to resolve. There are many things that can be done, that are linked together in various ways (directly or indirectly), but the path through the scenario is not fully defined by the designer. At many points there should be meaningful decisions to be made by the players, but they will likely remain in a ‘similar space’, so it is possible to predict (and thus prepare for) likely decisions.

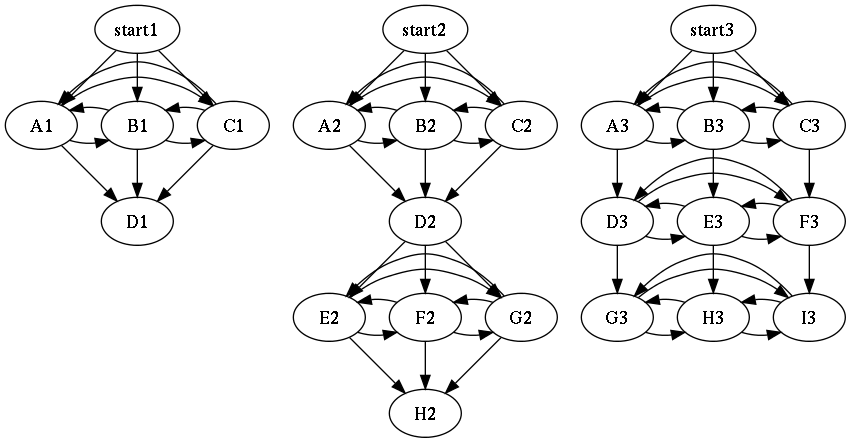

These scenarios are the focus of Justin’s Node-Based Scenario Design essay (same link as above); I’m going to steal a bit of thunder here and present some possible (and simple) scenario structures presented in that essay.

It should be evident that in the above structures that while there may be some fairly linear paths through the adventures (start1 -> A1 -> D1, done!) it is not necessarily the case that they play out that way. For instance, in the first example above, it might be necessary to visit A1, B1, and C1 in order to reach D1 at all (perhaps you need to accumulate three pieces of the MacGuffin to get the door to D1 to open). Instead of having a single path through the scenario, as with the linear scenario above:

Or even four paths, as with the semi-linear scenario above:

You now have six paths (listed below)… and only had to create the same number of encounters or events as the linear scenario (the denouement is implied). This requires a little more care, but not much more work

- Start1 -> A1 -> B1 -> C1 -> D1.

- Start1 -> A1 -> C1 -> B1 -> D1;

- Start1 -> B1 -> A1 -> C1 -> D1;

- Start1 -> B1 -> C1 -> A1 -> D1;

- Start1 -> C1 -> A1 -> B1 -> D1;

- Start1 -> C1 -> B1 -> A1 -> D1;

Mind you, you can do some more work and consider options based on the order the encounters are dealt with. For instance, a fight at B1 might alert the creatures at C1 (no surprise possible now, and possibly an alert sent to D1), but visiting C1 might prevent both of those alerts (but dealing with C1 before B1 might make it impossible to get from B1 to D1, so the PCs may have to revisit an area).

The scenario might instead require that only two encounters or events in (A1, B1, C1) must be resolved in order to move on (but the players may resolve all three if they want). This increases the number of paths from six to twelve. If only one must be resolved, but two or three are allowed, you’re up to fifteen.

Not bad, considering you prepare the same number of encounters or events as the linear example above.

The cohesive scenario structure has some very attractive features.

- There are multiple paths through the encounter/event set, potentially much larger than the number of encounters or events prepared. They do require some more thought, to ensure that the paths are viable and sensible.

- If prepared well, the encounters and events provide the players sufficient information to make meaningful choices as to their next actions (which step they want to take next on their path). It is no longer as simple as “go here or there? Flip a coin” (which I have seen done in play because the scenario did not provide enough information about what was going on).

- The large number of paths possible and the presence of meaningful choices allow the GM or scenario designer to better engage the players and keep them in the same area. This makes it much easier to prepare material for play by constraining where the players might go or what they might do – without having to apply hard limits.

Closing Comments

All in all, I really like the cohesive structure. The cohesive design lets me predict where and what my players will likely do without straitjacketing them into a specific path. This gives me more time to better develop material that will be used, instead of lightly preparing more material ‘just in case’ (or winging it, if I don’t have time for that much). I can still have some critical encounters and events (such as a specific climax, or a chokepoint in an adventure – which might be worked around if the players are clever (C2 could link directly to G2 above, allowing them to skip D2… which could change what happens later quite a bit).

This allows for some very dynamic play, a much more cohesive and coherent scenario than the open scenario structure, without appreciably more work than the linear scenario structure.

My solution on “Open” adventures was to have a set of possible hooks, and present them to the players at the END of the previous scenario/session and ask which option they would take. I could then build the adventure in detail.

I could come up with half a dozen possible hooks/rumors/whatever, the characters made any required divinations/gether information/NPC contacts to find out about the more obscure hooks, and the players got a real choice of any of these, but I only needed to prepare one.

It did mean that the game continued for a few minutes after the “final climactic battle”, but that’s fine.

I almost always do additional prep at the end of a session based on what I think the players and characters will do next. One thing I like about 4th ed is that preping an encounter is so easy I can make 2-3 times as many as I’ll use, and STILL put in less work than running 3.x was. Simple monster construction is GOOD.

Pingback: Node-Based Megadungeons | Keith Davies — In My Campaign - Keith's thoughts on RPG design and play.

Pingback: Anthony Node-Based Design | Keith Davies — In My Campaign - Keith's thoughts on RPG design and play.

Pingback: Review: Eureka (from Engine Publishing) | Keith Davies — In My Campaign - Keith's thoughts on RPG design and play.

This is a good analysis. Like you, I was never very happy with linear or “semi-linear” adventure paths — it’s easy for the GM, but somehow less satisfying to the players, who, regardless of what they think, HAVE been “railroaded” (or maybe “herded” is a better term) though the adventure. When I finally got to the point where I was comfortable enough as a GM to make my own decisions, I realized I could “do” something about that. But what to do? I then stumbled across the “”West Marches” campaign idea. If run properly, that truly DOES solve much of this issue; in effect creating a series of nodes and links that the players can explore at their discretion. BUT, the problem there is really three-fold; one, you need a LOT of players to make it work (and a couple of extra GMs wouldn’t hurt either), and most of us don’t have access to gaming groups that size; two, within the structure, the events in the various nodes still tend to be linear in nature, simply because you HAVE to have some kind of organization in there, and the GM is already doing a whole bunch of extra work designing the overall area of the West Marches; and, three, too many players aren’t actually “self-starters” (admittedly, all those linear adventures have trained them not to be, so not their fault), and you need people who will take the initiative and go explore to have an effective West Marches style of campaign; but a lot of them just sit around and wait to have information (“rumors”) fed to them to start them down some path or another. It takes quite a while to break that mind-set and get them to the point where they say; “I want to go do “A”!” instead of “Well, that merchant over there says “A” might be a good place to go.”

So the “nodal” adventure (but lets use your term, which is actually a better descriptive name for it), or cohesive adventure really solves so many of those issues — players can still get prodded into action with a rumor, but once in the action, the events drive them into decisions about the best way to proceed, which actually DOES give them free-will without either the Mobius Troll effect, or the hidden railroad effect, and yet still drives them to a satisfying denouement. All in all, an elegant solution for a frustrating problem that annoys both the GM and the players in different ways!

Thanks Jeff.

You might look up ‘point crawl’ (or ‘pointcrawl’, I’ve seen it both ways). It seems to be a more common expression. I think I picked up ‘node-based’ because I came at the idea via graph theory (i.e. nodes and edges), saw the expression used at The Alexandrian, and thought “yeah, that’s what I’m thinking about!”

I find nodal design leads to my having enough information for the next steps. That means I have the general shape of what I’m looking at (the setting, or the campaign, or the adventure/scenario) without miring me in detail until I need it. I know enough to give players hints about what’s around them, I know enough to be able to plan for even distant events and elements, without getting bogged down or wasting time on something that never happens. For example, I can lay the groundwork for the PCs to learn of the Forbidding Quagmire (I have a sense of what’s there and why the PCs might want to go there, and I can start giving hints and signs this is a place they might need) but don’t really spend much time on it until they decide to go there… and if they don’t, I haven’t spent a lot of time and effort on it.

The Node-Based Megadungeon doesn’t have all that much design time involved, honestly. I spent more time describing what I was doing than I did doing it. At least, as far as I took it, it’s not fully developed. However, I do have enough to know that the regions are distinct from each other and to know what they are, and that they are well-connected. Not only do I know what physical connections there are (how to physically navigate the megadungeon) but I can plot information and relationship connections between the regions. I have a clear sense of a complex environment with only a few hours work.

This applies at the broader levels too, of course. I can identify and get a sense at the high level so I can start building connections outside the immediate interest. This is usually much easier to do from the start than it is to do when discovering a need. “Um, Keith? How come we’ve never heard of this Really Big Thing that’s supposedly connected to the event that just happened?” can be an embarrassing question.

I found this resource by searching for Node Baed Scenario Design because I build a tool that aims to help GMs with that kind of scenario design. If you want you can check it out here http://warcry.de. its in early Beta Stage and might need some polishing, any feedback would be appeciated.

Ooh, this interests me greatly. I will check it out (was just at the site, but I’m in the middle of a programming project right now). Thanks for reaching out to me!